Update (22 August 2013): Winner! Damjan’s article was chosen as the winning entry. It was published this week in the August issue of the magazine. You can download a copy of the final version here (PDF, 765 kB).

Update (3 June 2013): Damjan (with Joan’s help) has written an extended article about our estimation method, which includes three bonus weddings! It has been submitted for the Young Statisticians Writing Competition run by Significance, a popular statistics magazine. You can download the article here (PDF, 175 kB).

When it came to inviting guests, we faced the classic dilemma. There were many people we wanted to invite, but we also had stay within the constraints of our venue, budget and desired level of intimacy. Should we invite many, and run the risk of ‘breaking the bank’? Or play it safe, but then likely end up with space to spare and miss out on inviting people we would love to have join us?

If our guests were all in Melbourne then the decision would be easy. People love weddings and are unlikely to decline an invitation, so we could easily predict our attendance. But our family and friends are not so conveniently located. Many of them were overseas and would be unlikely to make the wedding.

Luckily, our education has equipped us well for this situation! We could put our analytical skills to good use to optimise our invitation list. We created a probability model to get a handle on how many guests we were likely to have, and thus quantify the uncertainty with any particular choice of guest list. This allowed us settle on a guest list that was ‘just right’.

Method

Butleigh Wootton can seat up to 110 people comfortably, although it can be stretched to 120 with a bit of effort. Our aim was for about 100 people. This seemed quite aspirational, since our first attempt at a guest list had many more than this. We settled on aiming for somewhere between 100 and 110.

For each guest, we assigned a probability of attendance based on our subjective judgement. This was one of the following four values:

- 0.1 — for overseas guests who generally do not travel to Australia

- 0.5 — for overseas guests who love travelling and do it readily

- 0.8 — for overseas guests who seemed enthusiastic about a holiday to Australia

- 1.0 — for locals and overseas Melbournites who generally return for Christmas

Guests are generally invited in small groups, often in couples, sometimes in family units. Attendance of people within units is generally not independent and our model needs to capture this. We assumed that guests within a unit either attend or do not attend all together, as a unit. In other words, if we invited two parents and their two children, we assumed they would either all attend or none of them. Then across units, we assumed independence. That is, if we invite two friends and their respective partners, we assume that if one couple attends, it has no bearing on whether the other one does.

These assumptions induce a probability distribution for the total attendance. We can then examine this distribution to aid us in deciding a guest list. In particular, we can vary the invitation list until we obtain a distribution whose properties we are happy with.

Results

To emphasise that our numbers include the bride and groom (since we are interested in the total number of people), we will refer to attendees rather than guests.

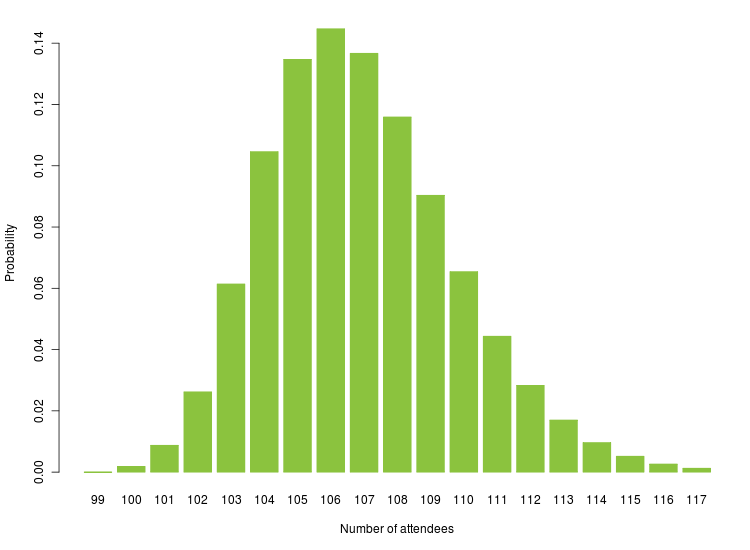

Our final list consisted of 139 attendees, in 82 units. After assigning probabilities, we obtained the distribution shown below.

The most likely attendance is 106, with a probability of about 14.5%. It is also approximately the median, although the distribution is slightly right-skewed. However, it is more useful to get a range of likely values from this. The central 95% probability interval is 102–113. The probability of more than 110 attendees (i.e. the probability of discomfort) is 11%, and the probability of more than 120 attendees (i.e. outgrowing our venue, leading to much embarrassment) is almost 0. These were numbers we were comfortable with. Alternative guests lists either omitted some key people or were too risky, so we decided to go with this one.

Discussion

The assigned probability values were by design slightly conservative, erring on assuming higher likelihood of attendance. The value of 1.0 is clearly conservative, but we expect is a good approximation of the true value. The other values are meant to be realistic, although we only based it on our judgement and not any hard data.

The independence structure adopted seems a very reasonable assumption for a wedding. Guest units correspond to people whose lives are either very intertwined, such as couples, or whose attendance together at a wedding is generally observed, such as families. Independence across units would also be expected, since in our society we lead fairly independent lives (at least amongst adults), and because the nature of the event is such that it will go on regardless of whether a guest accepts or declines the invitation.

Such assumptions would be more dubious for something like a teenage house party, where we would expect some degree of herding behaviour (someone is more likely to attend if they know their friends are as well), or for smaller events, where we expect a degree of cooperation (there’s no point in holding the event without a quorum).

Having received the bulk of replies now, we can gauge how well we did. The table below shows the attendees cross-tabulated by their assigned probability and their reply status.

| Probability class | Attending | Not attending | Awaiting reply |

| 0.1 | 0 | 26 | 7 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 95 | 4 | 1 |

| Total | 96 | 35 | 8 |

We can see that all of our probabilities seem to have been overestimates. We are currently standing at 96 confirmed attendees, and 8 still to reply. Going by the track record of the other guests, most of these will decline, which means we are well on the way to our desired number.

Go mathematics!